Robert McLean was born at Bethany in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1974. He graduated from the University of Canterbury in 2004 with an MA in political science and art theory. He returned to complete an MFA in creative writing in 2008. His poems, translations and articles have been published in a variety of print and electronic periodicals and anthologies, both locally and overseas. His first collection For the Coalition Dead was published by Kilmog Press in 2009.

Robert McLean was born at Bethany in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1974. He graduated from the University of Canterbury in 2004 with an MA in political science and art theory. He returned to complete an MFA in creative writing in 2008. His poems, translations and articles have been published in a variety of print and electronic periodicals and anthologies, both locally and overseas. His first collection For the Coalition Dead was published by Kilmog Press in 2009.

Robert, I think of you as having a strong interest in poetic form. Do you regard yourself as a formalist in the poetic sense?

I do have an interest in form for its own sake. Since I’m invested in functionality of meaning in a poem, I’m interested in the semantic ‘difference’ between, say, a Petrarchan and a Miltonic sonnet. There are many problems associated with my decision to write the way I have done. Whilst meter can serve to squeeze excess connotation from a saturated word, as Allen Tate often did, it can also make despicable rhetoric seem convincing, as do the relentless iambs in Pound’s Canto 81 – ‘Here error is all in the not done’; not my idea of humility. And since the printing press, the use of rhyme and meter as aide-memoire is almost redundant, which was the point of their development. Whilst nostalgia isn’t a concern for me, redundancy is a worry.

Since I’ve made a case against myself, I’ll try to answer it. Having witnessed first-hand the horrific consequences of unrestrained libidinal bloodlust, who could be surprised that the returning WWII US service men who also happened to write poems, especially those who took advantage of the G.I. Bill, turned to Augustan fixity in verse forms?

I grew up in New Zealand the 80s, when the Invisible Hand was given free reign to determine how much food ended up in our bellies – amongst other equally vital requisites of a dignified life. While I was at school, handing out the Communist Manifesto seemed more important than Jim Norcliffe parsing Wilfred Owen for School Certificate English, though I’m sure he did a fine job.

Imitative form never seemed to me an appropriate response. Besides, I started writing in my late 20s – anger had been replaced by sadness by then. What anger remains goes into my music. In short, I utilise non-organic form(s) for extra-poetic ends. Mediating reconciliations between sincerity of utterance and pre-determined patterns of relationship is utopian i.e. political. The integrity of every syllable is constitutive of structure, which is in turn dependant on maintaining the former to remain legitimate. To do so without semantic violence intimates my hope correlative social and inter-personal resolutions can also be possible. After all, the word is no less indeterminate or relative than the human.

So, yes: this is a socialist poetics – iambic pentameter quatrains reek of nostalgia and tradition, but they, for me, can also be read as anticipatory, should the reader so choose. This choice between signifying futurity or declension, rarely made in favour of the former, is the necessity and discrediting of my decision to write in such a way. I live with this.

I freely admit that to adhere to such a theory requires submission by its practitioner and relinquishment of much authority. It isn’t fun and I don’t like it. It is exhausting and unlikely to be sustainable. I find it painful. It involves exclusions and limits and refusals. It requires absolute scepticism of that into which I have most invested.

Most importantly, it demands that one takes full responsibility for the consequences of a poem, even, perhaps especially, for those which were not intended or desired. To write a necessary poem is the most difficult task I know. The standards outlined above are stringent and I have never met them.

You say “The standards outlined above are stringent and I have never met them”. Let us hope you do; but if it becomes apparent to you that you may never meet them, would you rather relax the standards, or go in a different poetic direction, or keep trying to meet them anyway?

If it became clear to me that meeting the standards was impossible, or, more likely, that I was falling ever further away from them, then I hope I’d have the grace to stop. Like I mentioned above, I don’t write for enjoyment or pleasure; and nor has my reading been hedonistic since Treasure Island and whatnot as a child.

It’s probably no coincidence that a fair proportion of the writers from whose words I’ve learnt most about better living and loving – Edgell Rickword, Laura Riding, Rimbaud etc – let it go. And of those whom I esteem who didn’t stop, most of them were far from profligate: Mallarmé, “the Hamlet of writing,” as Roland Barthes called him, published some sixty poems in thirty-six years – or Curnow. Besides, there are more than enough poems without me adding to the heap. The world is littered and noisy and by now I need very good reasons to publically raise my voice when what is needed is quiet.

In correspondence, you said “My poetics are an end point of other political and philosophical commitments and obligations”. What are those commitments and obligations, and how do your poetics emerge as their end point?

How I write is determined by two concerns: first, what poetry is (not what it has been) and what a poem can be; second, of what a responsible speech act ought to consist. To some extent, this can be understood as what my rights are and what my obligations must be.

Having spent seven years at University largely devoted to studying philosophy, I am well aware of the cogency of the ‘linguistic turn’ in thinking about thinking and the world. I also believe that whilst such destructive measures were necessary, now we need to reach tentatively across the space which has been cleared before it is filled with noise and consider constructive ways to rethink communicative possibilities which take into account the material conditions of existence without back-peddling to inappropriate strategies due to discomfort or difficulty. As Habermas wrote, “it is nigh impossible to think of ‘the ethical’ or moral consciousness outside of the sphere of language i.e. Communication”, and it is to discourse ethics I have turned as, for now, the best hope for solidarity and reconciliation through language in the public sphere.

I’m not a linguist, but if a phonological or lexical sign is the basic unit of language then the sentence is the basic unit of ‘discourse’. The linguistics of the sentence supports the theory of speech as an open-ended event. The premise is that human beings are unique rational (in terms of gathering as opposed to possessing knowledge) creatures that possess the ability to converse with each other without necessarily being dominated by coercion or instinct and recognises the ‘vulnerability’ of the individual.

There is interdependency between the individual and the collective in a shared ‘life-world’ and it is the communicative action of its members that produces a ‘language community’. ‘Life-world’ is the schema that you carry with you in an everyday sense, something that can be used to make judgments of reality and to help build a self-understanding of who you are. It is symbolic of how we may hope to orient ourselves as beings in relation to other beings. In the idealised ‘life-world’ that discourse ethics conceptualises, cases of disagreement ought to be brought to agreement by argument as much as possible.

Here, communicative action might be the mechanism by which agreement is brought about. What this means is that some kind of agreement is achieved that is considered fair and just by all individuals involved and nobody is forced to do what he/she is not convinced that he/she morally should do or tolerate: comprehensibility, knowledge-sharing, truthfulness, and consensus are requisites in this process. This is in contrast to strategic action, in which one actor seeks to influence the behaviour of another by means of the threat of sanctions or the prospect of gratification in order to cause the interaction.

There is no space to go into the details of the process, versions of which are readily available, but it is important that discourse ethics is founded not on the ‘I’, but more correctly on the ‘we’ and on the basis of a ‘mutual understanding’ between all parties. Self-expression is not its end. Within forms of communication there rests an implicit recognition of the other ‘I’. If the two ‘I’s’ can be referred to as subjects and there exists a discourse between those subjects then there exists an ‘inter’- subjectivity which has the potential for mutuality. We look for discourse ethics in the life-world of the ‘inter’ – and the ability that we possess to communicate through discourse and reach mutual understanding with each other, admitting that it can never be defining or exhaustive.

This leads to the second determinant of my poetics – what poetry is; or, in terms outlined above, what kind of life-world is poetry? My reply to this question is anti-honorific and anti-Romantic: it doesn’t raise poetry to Parnassus above street-language or scientific journals; nor does my answer amount to stating what I feel poetry should be and that much of this or that falls below a measure based on preference.

When it comes to poetry, I am not an idealist. Poetry is a social practice and institution. The practice involves producing poems and the institution legitimises or otherwise contextualises what its practitioners produce. Historically, both these functions have radically changed, as has the degree of independence poetry has had from other life-forms, so much so that apart from ‘Wittgenstein-esque’ ‘family resemblances’ and nominal continuity, little else connects, for example, Thus Skelton to Jack Spicer. Thus, poetry is what poetry-makers say it is.

Since people involved in poetry surely know the nature of the life-world of which they are constitutive, there is no need to go into great detail about its present characteristics. However, given that my fidelity to emancipatory speech ethics takes precedence over my investment in poetry, some aspects of the later and their bearing on the former are worth mentioning:

- The open-endedness of discourse clashes with the seemingly definitive presentation of the published poem. Given the lack of stringency in criticism, with which process could be reintroduced into poetry reading, this bluntness is even more exacerbated.

- The over-emphasis on license and rights by poets with respect to their own work denies any correlative obligations they could have outside the poetry-world.

- Comprehensibility, knowledge-sharing, truthfulness, and consensus are not lingua franca in practicing poetry, at least not at present.

- Strategic action, especially in terms of the prospect of gratification, say of ‘poetic experience’ however conceived, predominates in poetic practice.

I could go on, but clearly most of the principles involved in discourse ethics clash with those of at-present-poetry, but since my understandings of the former is idealist, albeit based on empiricism, and the later is pragmatic this is hardly unexpected. To state my current situation succinctly, it would be to say that when I write a poem, my first obligations are to responsible speech-making; only if these have been met do I then consider the rights of the poet and the peculiarities of the poetry-world.

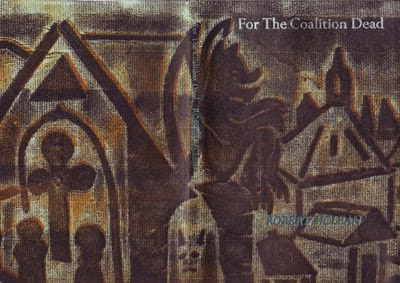

What would you like potential readers to know about your collection, “For The Coalition Dead”?

A preference for Moltmann over Kristeva would be helpful for the reader. Reconciliation, not schism, is dear to me. Various prosodies are employed from poem to poem, but if iambs and trochees too uncomfortably remind you of your father’s authority, especially if you consider that authority to be illegitimate, it would best be avoided. Apart from all that, it is lovely object into which Dean at Kilmog Press has put much time and energy. He deserves the support of people who want a sustainable alternative to the pulp culture of book-award winning presses.

What are your next priorities? Do you have further poetry projects planned out, or are you taking that as it comes?

The last poetry related projects on which I worked were seeing through to press another small collection ‘For Renato Curcio’, which is with Rob Lamb at Gumtree Press in Port Chalmers, and working on poems for my feature in the next issue of Poetry New Zealand, both of which involved revision and rewriting, not newly completed pieces. I haven’t written much at all since finishing my MFA with John Newton. If I do write another poem and continue to grope towards the standards I’ve set for myself, it seems to me the only way forward is to live better. There is an intimate connection between person and persona and what’s written. Being ever more attentive to my family, friends, and strangers, maintaining the distance of which Weil wrote that makes love, instead of possession, possible, and not over-privileging words – if I were able to do all that, then maybe I would move closer to writing the way I hope to write. But in so doing, I’d also move further away from having to write at all.

THE PATRIOT

Sweat beads my tonsured cranium:

above me I can hear a hum –

electrical. No longer dumb,

of what I know, I’ve told him some,

just not enough. My body’s numb –

but still he beats me (like a drum?):

blood freckles the linoleum.

Dispersed, I am the total of his sum.

He took a moment to explain

his expectations, which are plain:

to launder each inhuman stain

from where I am – what will remain

is emptiness except for pain

nuanced and measured out. He’ll drain

from me the substance I contain:

the truth is something that one cannot feign.

At first, I found it strange that he

could speak my language fluently,

and with a perfect accent. We

are countrymen. How could it be?

I never thought I’d live to see

this come to pass. Oh no, not me.

Belligerents, officially

we are engaged. We are our enemy.

He seems unfailingly polite –

he has no bark. Indeed, he’s quite

a gentleman, and yet his bite

is so severe. There’s no respite:

by now I must be quite a sight.

Back when I volunteered to fight

I could determine wrong from right,

but now I don’t know if it’s day or night.

So handsome in his uniform:

I watch him flick a switch – a swarm

of angry bees: I cannot form

a thought for sting and singe. The swarm

again, again, again – a warm

patch sops my pants. O he’s the storm

that rages when I can’t conform

to what he has established as the norm.

Consequently the rich smell

of shit and piss has filled the cell

I’ve absented. Somehow, I tell

him something true. Although I yell

and scream for God to stoop to quell

my agony, he knows I dwell

in his domain. I pray for Hell…

This is his job. He does it very well.

Each variation on his theme

is played just so. Thus I blaspheme:

mine was the blood Faustus saw stream

across the sky. He is supreme:

for whose voice is this I hear scream?

I must accept his will to deem

me thus reduced. And it would seem

not every nightmare has to be a dream.

Why did we let ourselves be swept

up by mere words? We could have kept

what land we had. Instead, we leapt

into the fray, repaid some debt

we thought we owed this beast that’d slept

within our civil state. Except

for Him, we men, all of us, stepped

in line. Watching us march, our mothers wept.

At last the stories that the old

ones used to tell make sense. Behold

the Man! More water…will it scold

or freeze? Of what I know, I’ve told

him some, perhaps too much. I’ve sold

a lie. I long for him to hold

me close, but all he does is fold

his arms and sigh. I feel so cold. So cold.

Book Availability

Kilmog Press books are available from Parsons Books Auckland, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and Kilmog Press directly (Kilmogpress at hotmail dot com).