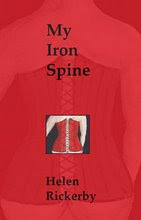

Helen Rickerby is a Wellington poet, publisher (through Seraph Press) and blogger whose second poetry collection, My Iron Spine, has been released to considerable acclaim. I interviewed her by email to mark the publication of My Iron Spine.

First of all, congratulations on the publication of My Iron Spine. What can you tell me about the book, and where can interested readers find more information, and copies to buy?

Thank you. I’m pretty excited about this book coming out – it’s been in process for a while, and I’m quite pleased with it. Also, I think I’ll be able to move on now to the next thing.

About My Iron Spine: well it’s divided into three sections, the first is autobiographical poems, which are arranged, more or less, chronologically. The biggest section is the middle, which contains biographical poems about women (and one man – sort of) from history. Most of them are written in the first person, and some of them are rather long – the longest is 11 pages. The final section kind of brings the other two together – in these poems I hang out with various women from history – I go swimming with Virginia Woolf, party with Katherine Mansfield, knit with Minnie Dean, and so forth. That section is a bit lighter, with more fun poems. Running loosely through the whole thing is the theme of the ‘iron spine’ – things that constrict or suffocate us, but which also make us stronger.

You can get more info from the HeadworX site, and also I’ve blogged a bit about writing it and the process of putting it togther.

Where to get it? It will be in ‘all good bookshops’, which means most of the independent folks around New Zealand. It’s now on Fishpond, but you could also contact HeadworX. And I have a bunch of copies to sell also, so you can always get one off me (helen.rickerbyATparadise.net.nz).

My Iron Spine is your second poetry collection, after Abstract Internal Furniture (2001). Without sounding too much like an essay question, in what ways are the books similar, and in what ways do they differ?

While I’m still very fond of Abstract Internal Furniture, I think that My Iron Spine is a step up in terms of my development as a poet. It’s more ambitious. I spent more time crafting the poems – tinkering with bits that weren’t working or could work better. I began to appreciate and use like alliteration and internal rhyme – which I’d previously been scared of – and I think the language is more playful. Also, it is more of a whole than the previous collection. It’s kind of hard for me to compare them – I’m sure I still have some of the same concerns, like the place of women in the world, and identity and stuff, and I suspect that the colour red features quite a bit in both.

I know you as a publisher, editor and blogger as well as a writer. Do you find that these different roles fit well together? Does your writing sometimes suffer because of the time and effort you need to put into the other roles (not to mention everything else that’s going on in your life)?

My writing does seem to suffer in relation to everything else – my full-time job is probably the main thing that gets in my way, and I’ve had to figure out tactics to make some time and headspace for creative writing. And sometimes publishing, editing and blogging do take up the time I might otherwise use for writing. But I also find those other things enormously valuable.

My involvement in JAAM Magazine is the most longstanding thing, and that’s been really important in exposing me to the work of lots of writers, and making connections with some of them. My Seraph Press publishing is intermittent, so when I’m working on something it takes up a lot of time, but often I’m not. I’m very proud of the books I’ve published, and think they are all books that really should be out there in the world.

Blogging is quite a new thing for me – I only started my blog late last year when I suddenly realised that blogging wasn’t just a waste of time, as I had suspected, but that it was an informal but public outlet for writing about stuff that I’m into – like poetry and publishing, and writing generally. While it can take a bit of time, I’ve found it really, really rewarding. And I think it’s actually helped my writing, of prosey things at least – made my writing more fluent. When you’re writing a blog post, you don’t have the pressure of writing something more formal, which is quite a freedom. But writing things down also makes you think about what you’re writing about in a deeper way than if you were just thinking about it, or writing about it in a journal, or even talking about it. The other really important thing I’ve got out of blogging is a sense of community from writing and reading blogs – Wellington writing bloggers all seem very friendly, and I’ve also made some poetry blog friends overseas. And I’ve now met some of the more local folks in real life.

One of the things that strikes me about My Iron Spine is that it’s a very clearly structured collection. Did you have the structure of the collection in mind before you wrote any of the poems, or did it evolve as you went along?

It evolved as I went along – it grew out of what I was writing. I noticed I’d been writing some poems about real people, and thought I’d write more. And then at some point I started seeing a structure, and then I wrote some more poems that fitted in with what I was doing. I wrote most of it in a year that I was fortunate enough to be able to take off work (pre-mortgage, you understand), and as well as writing, I was reading a lot of collections of poetry. And the ones that struck me the most were ones that worked as a whole, rather than just being a ragbag of poems, because they set up resonances that made the whole even stronger than its parts. It’s something I’ve become really interested in.

Also, I find it easier to write when I have a kind of poetic project – I guess in Abstract Internal Furniture my series of Theodora poems were a bit like that, and I’m now working on poems which are loosely based around ideas of cinema. It means you don’t have to start from scratch each time, and you can really explore and develop some ideas.

The middle section of My Iron Spine features biographical poems about a number of well-known women, and then, in the third section, the poet interacts with these women. Abstract Internal Furniture also features biographical poems. Why does writing biographical poems appeal to you, and what balance of research and imagination goes into them?

To be honest, I haven’t really thought about that – I’ve thought about why I’m interested in reading biographies, but not why I’ve enjoyed writing these poems. I’m really interested in people’s lives, and in biography, which isn’t quite the same thing as someone’s actual life – it’s an attempt to turn someone’s life into a coherent narrative. I guess a biography is to a person what a map is to place. I suppose these poems are like that too. I think I’ve enjoyed writing these poems because I enjoyed imagining the character, how they might sound. But mainly to interpret them, highlight aspects of their story or personality. I also like stealing ideas from elsewhere – possibly I don’t have enough of my own.

For some of them I did a lot of research, but I found that if I knew too much in the beginning, then in made it harder to make a poem out of it. I wrote some poems before I did research, and then had to alter them. There’s one in the voice of John Middleton Murry, Katherine Mansfield’s husband. I knew a lot about them both when I first wrote it, but then I read his autobiography, and then I rewrote it a bit, because I felt I’d been too hard on him. I’ve tried to evoke these people in ways that might be true, but there’s a lot of creation, especially about what they might have been thinking. You really can’t know.

Which poets have had the most influence on your work, and which poets do you most enjoy reading? (Of course, these might be one and the same.)

Sometimes they’re the same, and sometime quite different. For example, Scott Kendrick, whose work I’ve published, is one of my favourite writers, but we’re doing such different things in our writing – in style at least. There are very few poets that I know are influences on me – Anne Carson is one, and Margaret Atwood another, and I was trying to be influenced something in the style of T S Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’ when I wrote parts of ‘Empress Elisabeth’ – but I’m sure many others have been also. Sylvia Plath almost certainly. I’ve also very much enjoyed Anna Jackson, Jenny Powell-Chalmers, James K Baxter, Ursula Bethell, Vivienne Plumb, Dinah Hawken, Anne Sexton, Fleur Adcock, T S Eliot, Stevie Smith, Sharon Olds. You will notice that they’re mostly women, which isn’t deliberate, and many of them are people I know. I guess you put special effort into reading work by people you know, which I think is usually rewarded by getting extra out of it.

How about prose writers?

Again, Margaret Atwood, though I haven’t read as much of work in the last 10 years, because I overdosed by writing a masters thesis on her (‘Fairytale intertextuality in the fiction of Margaret Atwood’). Jeanette Winterson is a favourite, and her novel The Passion is a total inspiration to me. If I could have written any book in the world, it would be that one. Other favs include Douglas Coupland, Charles Dickens, Angela Carter, the Brontës…

What writing projects do you have on the go at the moment? (If you’re prepared to talk about them, of course: I know I don’t always want to talk about what I’m working on right now.)

The main think I’m working on is the cinema poems I mentioned earlier. I’ve written quite a few, but I feel like I’m still in an early stage with these. I’m hoping they will turn into a collection. Once I’d finished My Iron Spine I felt like I needed to go in a different direction, and leave the biographical/narrative poems for a while. I felt the same after Abstract Internal Furniture – I felt like I could write a parody of a Helen Rickerby/Theodora poem, and that it was time to write something a little different. Some of the cinema poems are still narrative, but others are more surreal or impressionistic.

A tough one to end on: if you had to choose three words to describe your writing, what would they be?

That’s very, very hard. I don’t think I know my poetry well enough from the outside to really be able to say. Last week someone I don’t really know, who had heard me read at the Winter Readings, told me that my poetry was like nothing he’d come across before (‘in a good way’ he qualified), and said it was intelligent. And one always likes to be thought of as intelligent, though I don’t always deserve it. Other people have said that my work is accessible, which also isn’t always true. I’d like it to be intricate, beautiful, layered, mythic, and so that’s something to aim for, and that’s more than three words…