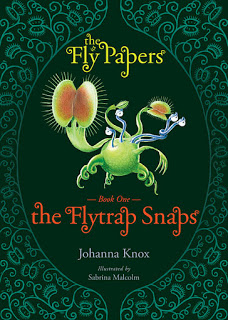

Johanna Knox is the author of an intriguing new children’s book series for 8-12 year olds – The Fly Papers. The first book, recently released, is The Flytrap Snaps.

Described in reviews as everything from ‘fresh’ and ‘funny’, to ‘quirky’ ‘madcap’, and ‘bizarre’, this fast-paced mystery adventure is set in a booming movie industry town called Filmington. It features resourceful children, a ruthless venture capitalist, and a plethora of walking, talking carnivorous plants, who’ve been genetically engineered to star in horror movies.

Johanna has spent much of her career writing for museums, as well as for magazines, youth websites, and educational publications. However, her passion has always been fiction. This is her first published novel, and she has teamed up with her partner Walter Moala, a graphic designer, to bring it out under their own imprint – Hinterlands.

How did the idea to write The Fly Papers come about?

About eight years ago, our young son got obsessed with carnivorous plants, so we bought him a small collection of different species for Christmas. Then I think I became one of those dreadful parents who takes over their child’s interest! His obsession wore off (hopefully I didn’t smother it), but mine stayed.

I was fascinated with each plant’s personality. They felt more like pets than pot plants, and I used to wonder what they’d be like if they became animate.

I started a story about them but wasn’t sure where it was going, and put it aside. I came back to it, ages later, after the global financial crisis had hit. By then I’d thought a lot about debt, and consumerism, and financial exploitation. I melded those themes with the carnivorous plant story, and suddenly I was excited about it again.

It’s perfectly possible to read The Flytrap Snaps for fun without dwelling on financial issues, but those ideas are there, if readers care to delve into them. I’d like to think the book could make a good discussion starter if parents wanted to talk about money with their children.

How long did it take for the idea to become a published reality?

The year before last, a whole lot of things came together and Walter and I found ourselves in a position to do what we’d always talked about, which was publish our own books. We figured, ‘it’s now or never’, and it made sense to start with this carnivorous plant fiction series.

I’ve got a copy of The Flytrap Snaps, in front of me, and it looks great! How much effort did it take to get that superb production quality?

Thank you for saying so!

Well, Walter really drove the production process. We felt that if we were investing so much into the books, the production values should reflect that, and as self publishers, we could control the outcome.

Walter worked closely with MWGraphics on production. For example they collated all the illustrations and sample text onto A2 pages and tested the ink coverage on the paper stock on the printing press. It doesn’t get more accurate than that. We knew exactly what we were going to get before we went to print.

Walter has a great (and longstanding) relationship with MWGraphics, and they really went the extra mile to help us get a result that they were proud of too.

A major part of the appeal of the book is the illustrations by Sabrina Malcolm. How did Sabrina come on board as the illustrator?

From the start, we wanted the books illustrated. We were inspired by movies like Little Shop of Horrors, and old B-grade movie posters. We began to imagine what the plants could look like but, as Walter says, we needed the safe hands of a great illustrator who knew the subject, but would also add their own ideas.

We’d worked with Sabrina before, back when Walter was at Huia Publishers, and I was also doing a bit of children’s book editing for them.

Walter and I both worked on the Huia picture book Koro’s Medicine by Melanie Drewery. We were looking for an illustrator for it, and a friend recommended this woman Sabrina who had a background in botanical illustration – ideal for a book about native medicinal plants. So she came on board.

We loved working with her, and the book ended up as a finalist in the NZ Post Children’s Book Awards, so she did a great job.

Some years later we reconnected with Sabrina when our respective sons became good friends. When we needed an illustrator for a novel about carnivorous plants, it was a no-brainer to approach her, and that’s when we discovered that unbeknown to us she’d been harbouring a deep fascination with carnivorous plants for years!

Will Sabrina be illustrating the whole series?

I hope so! They’re a big part of The Fly Papers’ identity.

The Flytrap Snaps is published by Hinterlands. What made you decide to take this route to publication?

Walter and I had been running our business, Hinterlands, for years, contracting out writing and design services, and usually working for separate clients. The book series was a way to combine our experience and skills on a single project that we could take full responsibility for.

Do you envisage that Hinterlands will publish work by other authors?

We’ve always had that in mind as a goal, and we’ll look into it further down the track.

I was impressed by the list of bookshops that carry The Flytrap Snaps (on the right of the linked page). As a new publisher, how have you gone about getting this wide distribution? Was it difficult to achieve?

Before publication, we did a road trip through sections of the North Island, gauging and drumming up interest at independent bookshops. After it was published, we did our best to get in touch with as many of those shops – and other independents – as possible, to see if they’d stock it. And it’s ongoing. We’re constantly working on getting it into more places. But that does take time.

It’s been all about lots of emailing, plus in-person promotion to bookstores near us. We’ve also had kind friends and associates in other parts of the country help promote it in their locales. Plus whenever we go on a trip, we make sure we take a few books to show the local shop.

Forming good relationships with independent booksellers is really a holy grail for us. They have such a passion for books and for the whole process of matching books with people. They’re the ones who are likely to hand-sell your book if they like it … and that’s what you need when you’re starting out and don’t have a name.

The more booksellers we can find who decide they actually like our book and want to put it in the hands of customers they think would like it too, the better.

They don’t have to be independent booksellers of course – there are stores in chains where the individuals running it have the same ethic. Someone told me you’ll often find that kind of attitude in chain stores in small towns, where they may be the only bookshop around, so they become an extra special part of their community.

All that said, we’re discovering how brilliant and supportive libraries and librarians can be to deal with, too!

The advent of ebooks has had a big impact on adult fiction. Has it had the same effect on children’s and YA fiction? Is The Flytrap Snaps available as an ebook, or if not, do you plan to turn it into an ebook?

I think ebooks are taking longer to take off in the world of children’s and YA literature, but it’s definitely happening.

We do plan to turn it (and the other books in The Fly Papers series) into ebooks in the not-so-distant future.

Walter and I love printed books though! We’re not luddites by any stretch, but we’ve both always loved the look and feel and smell of printed books, and somehow they feel more real, more substantial and more permanent.

When I have a new book out, and given my other commitments, I find it difficult to maintain the balance between writing and promotion – put another way, it’s hard to get writing done when there’s a book to promote. If you have a secret to maintaining that balance, I’d love to find out what it is!

Me? I’ve been searching for balance – any kind of balance – since I can remember. Maybe the balance is just in the constant seesawing.

It’s funny how this is such a major topic of conversation when writers get together! We always seem to be comparing notes about how we have or haven’t found balance of one sort or another, whether it’s writing vs promotion, writing for love vs writing for money, or writing anything vs family commitments!

To get back to your original question, promotion eats up a lot of time, and so does distribution. Even just the packaging, invoicing and mailing. All the jobs that individually only take a few minutes, really add up.

A wise friend recently told me how she likes to make sure she never lets a whole day get totally consumed by long lists of small jobs (like promotion and admin tasks). Instead she makes sure that every single day, she spends at least a bit of time making headway on a large scale job (like a novel manuscript).

I’ve tried to force myself to do that lately, and it’s really helpful. Otherwise, it’s too easy to put off the large-scale tasks, thinking I’ll wait till I have a day clear of small tasks. But that day never comes!

A slightly different question: do you enjoy the whole publishing and promotional side of the business, or is it a necessary evil that one has to undergo?

Hmm … it’s definitely an interesting learning curve, and it’s satisfying overseeing the entire process. On the other hand, sometimes it would be nice to have that extra support of an external publisher.

As well as continuing work on The Fly Papers, I’ve recently been commissioned by another publisher to write a book.

I’m finding this a very different experience. Just having the external validation of someone saying, ‘We believe that you can do this book,’ is so reassuring. Whereas when you self publish you need an amount of inner self-belief that it’s frankly impossible to maintain all the time.

When I can’t maintain it I have to go onto auto-pilot, and think, okay, whether I believe in this project or not right now, I just have to keep trudging along this path I’ve mapped out … keep putting one foot in front of the other.

When it comes to the actual promotion, it can be deeply uncomfortable trumpeting your own book, especially when it’s effectively self published. It’s like I have to split myself into two selves – the writer-me and the promoter-me. It’s not always a happy split, either.

The writer-me (which I’d suggest is much closer to the real me!) just wants to immerse myself in the story, and have a handful of people like the story for its own sake, and ignore all practicalities … But the promoter-me has to block out any investment in people liking the book for any reason other than that it’s a business venture, and we need to make some money off it! (And that means I have to get LOTS of people to like it.)

Right now, you’re really interviewing both those people, and this is an odd feeling. The writer-me is a wear-my-heart-on-my-sleeve kind of person who wants to answer everything you’re asking me fully and frankly, and not a little self-deprecatingly. But as I reply I’ve got the promoter-me in my head, interjecting sometimes with ‘you can’t say this…’ and ‘make sure you slip in something about that …’

On a lighter note, one fun thing about promoting this book is that I get to talk a lot about carnivorous plants, especially to kids. I love it that anywhere I set up a display or talk, there are always one or two children who seem so enthralled that they can’t leave.

They will come, look at the plants, and then wander off (or be dragged off) … Then a few minutes or half an hour later they’re back … And then later they’re back again, and each time they think up new questions to ask. These plants really seem to get under the skin of some children.

Can you reveal a bit about the second book in the series?

Well it’s coming out next year, and it has a lot of stunt wrestlers in it, as well as carnivorous plants.

One final question: what’s the best thing about being a writer?

Not having to sit around wishing I was a writer, I suppose, which I would … if I wasn’t.

On the other hand, occasionally, when things aren’t going so well, I dream about chucking it all in and becoming a florist or a herbalist or a perfumer. I reckon lots of people must have fantasy alter-ego jobs that they float away to when things get too much in their real job.

Anything else you’d like to say?

Well, the promoter-me says I have to tell you that The Flytrap Snaps makes a really good gift for bright, inquisitive children when packaged up with a real Venus flytrap from your local garden centre. Especially as in the back of the book you’ll find detailed instructions for looking after your own Venus flytrap!