Kathleen Jones is a biographer, poet and journalist based in the English Lake District. Her partner is a sculptor working in Italy, and several members of her family live in New Zealand, so she spends quite a lot of time travelling.

Kathleen started writing as a teenager, contributing to local papers and teenage magazines. She wrote a lot of bad poetry, married very young and went to live in the Middle East where she started working for the Qatar Broadcasting Corporation as a presenter and script-writer. When she came back to England she freelanced for the BBC and this led to her first biography. She’s now written about 11 books including poetry as well as journalism and short stories. Kathleen also tutors creative writing and is currently a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Lancaster University.

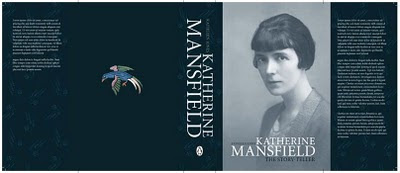

You are known for your biographies of woman writers, including Margaret Cavendish, Christina Rossetti and Catherine Cookson. August 2010 sees the publication of The Storyteller, your new biography of Katherine Mansfield. What drew you to Katherine Mansfield as the subject for a biography?

I’ve loved her work and been fascinated by her life story since I was a teenager. I found the John Middleton Murry edition of her Journal in a second hand book bin when I was 17, and I’ve carried it around everywhere even though it’s in pieces now.

Even then I was aware that there was a lot of myth-making, and everything I read about her just made me more determined to find out what really happened. There were mysteries, and Katherine herself was portrayed as either a rather waspish good-time girl, or a sentimental heroine wasting away like someone in a Victorian novel. I wanted to know what she was really like.

As one might expect of such a major figure in the New Zealand literary scene, Katherine Mansfield has been the subject of a lot of biographies and other non-fiction books. If someone asked “why should I read your Katherine Mansfield biography rather than one of the others?”, how would you answer?

I would say “Read mine because it’s the only biography to be written since all the documents relating to Katherine and her husband John Murry became available in the public domain. Katherine’s letters and notebooks have all been transcribed and printed and the diaries and letters of John Murry are now also in the Alexander Turnbull Library. Additionally I’ve had the help of the family who still have quite a lot of material relating to both Mansfield and Murry. There’s a lot of new information. It’s significant that most of the leading figures in the story are now dead, so information is less likely to be withheld to protect people.”

I’ve also tried to write a book that’s good to read. I want my characters to live in the mind of the reader and come off the page as vividly as they would in a novel.

The Storyteller is being published by Penguin New Zealand. I know of many New Zealand writers who have been published in the UK, but this is the first time I’ve heard of the publishing process going in the opposite direction. How have you found that process of being published half a world away, and what promotion will you be doing for the book while you’re in New Zealand?

Yes, it does seem strange. Initially it was a partnership between a UK publisher and Penguin NZ but the ‘publishing crash’ has had a huge impact over here and literary biographies have been dropped like hot cakes – rather than selling like them. Fortunately, Geoff Walker at Penguin has been hugely enthusiastic about the book and was very happy to go ahead. I’ve got great editors and the whole thing has been a lovely experience. It’s amazing how much can be done by email!

I’m arriving in New Zealand on the 5th August and there are several events lined up – there’s a talk and discussion with Sarah Sandley at the Women’s Bookshop in Auckland on the 10th August at 6pm, in Wellington Thursday 19th for a New Zealand Book Council event, and then I’m at Christchurch Literature Festival for two events: Friday 10 September, 11.00am–12.00pm, Past Lives Session with Jeffrey Paparoa Holman & Paul Millar, and Sunday 12 September, 12.30-1.30pm, a session on Katherine Mansfield (with Harry Ricketts).

I’m also available for talks, discussions, readings and workshops and if there’s anyone out there who wants to organise a small event, I’d be happy to be involved.

Of your previous biography subjects, I suspect that Margaret Cavendish will be least known to my readers, just as she was least known to me. I was fascinated to read about the scope of her achievements, and also that she had written an early science fiction/utopian novel, antedating Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. How did you find out about Margaret Cavendish, and what was the lasting impression she left on you?

Margaret Cavendish was one of the earliest women (1641) to publish her work at a time when it was considered immoral for women even to write! I found a quotation by her when I was researching a programme for the BBC. She basically said that it was no wonder men didn’t consider women to be their equals because women were so ignorant and silly. The cure, she said, was education and while women continued to be educated at home by their mothers or governesses it would never change; ‘Women breeding up women – one fool breeding up another’.

I was so intrigued by her unique voice, I tried to find out more. It was a detective trail that ended with the biography. She was a shy, difficult, rather neurotic person, living at a time when women had very little freedom, but her courage was immense and I’ll always remember how she endured mockery and abuse with dignity, for saying that women ought to have equality.

More generally, why do you like writing biographies?

I’m fascinated by people’s lives. You could say that biography is a kind of up-market Hello! magazine – there’s an element of voyeurism, literary lace-curtain twitching about it however scholarly you are. But nothing beats the buzz you get, sitting in an archive, reading a love letter – perhaps Wordsworth to his wife – or turning the pages of Katherine Mansfield’s journals. You’re touching the same paper they touched, reading the words they inked on the page all those years ago.

According to Wikipedia, you “escaped to London as a teenager in order to become a writer”. Why was this necessary, and what led you to return from London to the North?

I was brought up on a small farm in a remote part of the United Kingdom – many of the local people had never been more than 30 miles away from home in their entire lives. Apart from breeding sheep, nothing much else went on. I loved the landscape and the isolation, so it was difficult to leave, but I knew I had to go in order to become a writer. You need contact with other writers – Katherine Mansfield had to leave New Zealand to do it.

Once I’d become a writer and established myself, it was easier to return home, but I still have to go to London regularly because that’s where it all happens.

I imagine that both environments: London, and Cumbria where you now live, provide benefits to writers. If you were a young writer growing up in Cumbria, or indeed any comparatively remote rural location, today, would you advise them to head to London to start their writing career?

Yes, I would. I think you need to get away to get some perspective on your own life. You also need ‘input’. If you stay in a small community there’s always a danger that you become a big fish in a little pond and never really achieve what you’re capable of. And you need to find your way around the world of books so that people know who you are.

The days when you could write and keep a low profile, relying on publishers and bookshops to sell the product are over – publishers expect you to go out and network to publicise your books. We have to learn to be ambassadors for our own work. The shy, reclusive author is at a disadvantage.

You write poetry and fiction as well as non-fiction. What place does each of these have in your writing?

I like all the different genres, though I’d probably have been more successful if I’d stuck to only one. It depends on the idea – some ideas are only suitable for a poem, other will stretch to a short story, non-fiction projects demand a much greater investment in time and research and have to be chosen quite carefully. If you’re going to write a biography you have to like someone enough to spend a couple of years in their company.

Which writers have been most influential on your own writing, and which are your personal favourites? Are there any writers who haven’t received the publicity they deserve that you’d like to recommend?

Apart from Katherine Mansfield’s Journal, I also read Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea as a teenager and it taught me a lot about getting away from traditional narrative. The other really influential book was Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller… and for the same reason. They taught me a lot about multiple narrative threads and parallel texts. If you put two – or more – stories together in the right way they can double up on the meaning in the same way that poetry does.

It will sound a bit weird, but the other book that influenced me was Chaos, by James Gleick, because it demolished the traditional way we thought about the universe and how it’s ordered. I suddenly realised that everything – absolutely everything – is made out of beautiful numerical patterns that keep evolving and changing because they are Imperfect and Incomplete.

It seemed to offer ideas about the patterning of words in poetry and prose – and it reinforced the conviction that a narrative or a poem has to be open ended with a sense of evolving, not rounded off and complete in a dead-end sort of way that offers the reader no way of carrying the story on. It taught me that creativity comes out of chaos. Does this make any sense?

There are hundreds of good authors out there who never get the readers they deserve. I know you’ve got lots in New Zealand who never make it across the ocean. It is such a pity. Marketing is everything these days. One really good author I’ve come across recently is Amy Sackville, whose first novel The Still Point is utterly ravishing.

Do you have a plan for how your writing career will continue to unfold? If so, and if it isn’t a secret, where do you see yourself and your writing in five years’ time?

The Mansfield biography has been very hard work – so I’m taking a rest and concentrating on fiction for a while. I would like to publish more fiction – it’s too easy to become ‘pigeon-holed’ in a particular genre. Just now I’ve got a couple of plots burning away at the back of my head and I need to see if I can get either of them to work.