I have known Trevor Reeves for many years, firstly through our joint involvement in environmental activism and the Values Party during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and later through his work as a poet, publisher and editor of the literary magazine Southern Ocean Review, in which I had several poems and a couple of short stories published during the course of its 50 issues. When I heard that Trevor was bringing Southern Ocean Review to a close, I thought it would be a good time to talk with him for this blog.

Trevor, readers of this blog are most likely to know you for your recent poetry and as the editor of Southern Ocean Review. They may not have heard of Caveman Press and all the other things you’ve been involved with as a publisher, editor and writer. Can you tell us how you got started with writing, publishing and so forth, and what your major ventures have been?

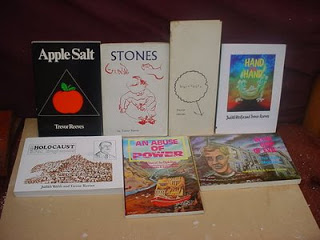

Caveman Press started up in 1971 – I still don’t know why I chose the name, but it seemed to go down well. I was given an old Golding Disc Inker printing press (letter press) and proceeded to teach myself how to print books on it. The first was a book called “Skyhook” – poems by Lindsay Smith. He now lives in Australia and I am still in touch with him. He was quite an influence in my own writing and my books ‘Stones’ and ‘Apple Salt’ came later. Other books followed in close succession as sales in those days were good. Alan Loney set his own book then – now a collector’s item. The late Dennis List then Murray Edmond and two of Hone Tuwhare’s books; ‘Sapwood and Milk’ and ‘Something Nothing’ – also a new edition of his ‘Come Rain Hail’ came next. Later in the 1970’s, we branched into general books. They were books on architecture, politics, humour, health, etc. It was a busy time. We also did four issues of a literary magazine, ‘Cave’ which contained some overseas writers, including Charles Bukowski.

Since 1996 you’ve been the editor of Southern Ocean Review, which appeared with impressive regularity, four issues per year, right up to Issue 50 in January 2009. What led to your decision to make Issue 50 the final issue?

It’s done its dash and is a lot of work anyway. It was fun to do, of course and online a long time before any other magazines were. The print version started at #3 and carried on right until the end. That’s 47 separate issues; the largest being 84 pages but most around 64 pages. We asked for submissions from all around the world. However, we published plenty of NZ content, too. People got around to sending their best work too, which was pleasing. We had a policy, too that every work was illustrated – by Judith Wolfe, co-editor. All issues are still on line at www.book.co.nz and will be for some time yet. l have the print versions available for anyone who wants copies. The magazine survived without any subsidy or grants, which resulted in a bit of a struggle to keep it going, but we managed. One of the joys of the magazine for me was the reviews section. There were always plenty of books to a short review or notice for. We were privileged to get review copies from Auckland University Press and other well known publishers of poetry, stories and novels. Victoria University Press never came up with any despite being continually asked, but that’s the way it goes, I guess. My main task as I saw it was to give each book a good plug; realising that people have very different tastes.

I didn’t know that you wrote fiction until I reviewed your short story collection Breaker Breaker for JAAM magazine. Is writing fiction something you’ve been doing all along, or is it a comparatively recent development?

I have always been interested in short story writing. My earliest pieces were science fiction ones and I remember my first one being published in the centenary Otago University Review, in, I think it was, 1968. Short story writing was a rigid discipline for me – beginning/middle/end which was good for me and I enjoyed the constraints. Usually, I would dream up a plot and sit on it for quite some time; years, even. Then I would write it up in a couple of hours, usually. I sent them all around the world and they generally got a good reception, which was pleasing. Gathering them all together, I published them in the book; “Breaker Breaker”.

I like your poetry a lot. I was trying to think of a way of characterising it to someone who hasn’t read your work, and the best I could come up with was “experimental but accessible”: it’s not always straightforward, but it is always rewarding. Is that a fair or useful description? How would you describe your own poetry?

My first book was ‘Hibiscuits’ published in England in 1970. That contained some pretty traditional poems mainly about nature and domesticity. Next was “Stones” with Bill Mackay illustrating it. I became a fan of artworks illustrating poetry early on. In 1975 came ‘Apple Salt’ which started off with poems that were pretty traditional then I began experimenting, with ‘found poems’ etc. Then I stopped writing poems altogether to concentrate on commercial art, to try to earn a living etc, and also to research non-fiction books. Then, from 1993, I began to get some stories together and experiment further with poetry. I liked the idea of rhapsodic lines, no beginning middle or end, in a kind of ‘formlessness’ like random speech. With my poems I like to relate as much as I can to ordinary speech and ordinary situations etc.

Who or what – in terms of individual poets, groups of poets, or particular magazines – were the main influence on you when you started writing and publishing poetry? Have those influences changed over the years?

I followed and contributed to most magazines that emerged in the 1970’s. New Zealand influences for me were Tony Beyer, Dave Mitchell, R A K Mason, J K Baxter, Hone Tuwhare etc. I didn’t follow any ‘group’ as such but was involved in most of them. I think there are more poets than ever now, though sales of poetry books have dropped as people have been accessing the internet more. Certainly, publishing small volumes of poetry as I have done over the years doesn’t pay off now but I am pleased to have published the books of many, including Murray Edmond, the late Dennis List and Hone Tuwhare, the late James K Baxter, Alistair Paterson and many others.

Do you enjoy performing your own poetry, or listening to other poets performing theirs?

Yes, I do, or rather, I did. I did quite a lot of readings around the country in those days. Most enjoyable were in Auckland, with people like Dave Mitchell, Tony Beyer, Peter Olds and many others. I would love to have read overseas, but never got the chance.

It’s been 16 years now since I moved from Dunedin to Wellington – alarmingly long! – but from what I can make out, the Dunedin literary scene is quite lively at the moment. All the same, it seems to me that authors from the southern South Island – maybe from the whole South Island – don’t get as much attention as they deserve in the rest of the country. Do you agree, and what (if anything) could or should be done about it?

I have, and always have had, a wider outlook. And since the onset of the internet, places seem to have become even less relevant in terms of distance. The ‘Dunedin Scene’ has always been lively as has been most other centres. Writers in Auckland have always considered themselves more important of course but that’s just natural, being a bigger centre for writing. I don’t think anything can really ‘be done about it’ – I mean, what, and what for?

Finally, where to next for Trevor Reeves as a writer?

Who knows? I have written in just about every style there is, except a novel and I’m in no hurry to do that. I am back on to the poems now, with my ‘sequences’. I published a book of those, called ‘Hand in Hand’ – which was a collaboration with Judith Wolfe, artist. Before that there were other collaborations with Judith Wolfe, but with non-fiction books. “An Abuse of Power” was the first one, about the building of the Clyde dam. The second was ‘In the Grip of Evil’ – our investigation into the Bain murders – illustrated. This drew threats of a legal action against us but nothing happened. Something may happen in the future, who knows… The next book was ‘Nazi Holocaust’ a cartoon book of the holocaust, in Nazi Germany. This was a harrowing book to do and took a lot of research. Lately, I’ve been on to 6-word ‘American Haikus’. These are strung out in sequences of eight stanzas. These take a while to do, but are nice as it makes me think of the principle of the aphorism and has strict rules. I am not editing anything any more; nor publishing the works of others, either. I have done my share of journalism, editing ‘free’ papers and writing for them, so no more of that.