I’m a fan of recently-established Dunedin ebook publisher Rosa Mira Books, for several reasons:

– I like the publisher, Penelope Todd

– I like the idea of a New Zealand publisher tackling ebooks head-on, rather than side-stepping nervously around them, and I want to see that effort succeed

– They publish good books.

But there is a fragment of self-interest in there as well. Rosa Mira Books launched with the short story collection Slightly Peculiar Love Stories, which includes my story “Said Sheree” and lots of fine stories from New Zealand and international authors.

One of my favourite stories in the collection is “The Ache”, by Argentine writer Elena Bossi, translated into English by Georgia Birnie. It distils romantic yearning down into two lovely pages.

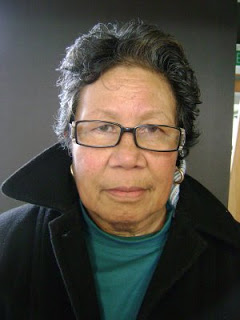

I recently asked Elena three questions about her writing, and here are her answers. English is not Elena’s first language, and so she asked me to tidy up her answers for an audience of predominantly native English speakers. I have tried to do so without losing the flavour of her replies.

Three Questions For Elena Bossi

1. Besides the quality of the fiction, one of the things I like the most about “Slightly Peculiar Love Stories” is the wide range of countries the authors come from. How did a writer from Argentina become involved in an anthology of love stories edited by a New Zealander?

I knew Penelope, and many of the other “Peculiar” writers, from the International Writing Program in Iowa in 2007. Of course, all of them read me in English translations. That’s it. Penelope and Kavery Nambisan (from India) helped me a lot with translations. As did two different students from the Translation Workshop of the University of Iowa.

2. Your story “The Ache”, which is one of my favourites in the anthology, was translated from the original Spanish into English by Georgia Birnie. Do you enjoy the process of having your work translated?

I really do like the process of translation, it is actually like reading another story again and now I can read it as other. It is very “peculiar” to see our own words as the words of others and this make me think that our words are always strange in some way. We have some strange insight which is a little scary too.

3. In New Zealand at least, the publishing industry is changing rapidly, and all but the best-established writers have to be adaptable to keep getting their work published. Is now a good time to be a writer in Argentina?

I think a better time to be a writer in Argentina was during the ’60s and the ’70s. After this time, and also because of the military government, a commercial change began which concentrated all the little publishers we had into big ones and began to be more interested in selling than in literature. The figure of the publisher/editor disappeared and a regular manager took the place.

Now, little by little, big international publishers are losing space and a lot of more or less familiar publishing houses are coming again. So I hope things are going to change a little but the volume in our bookstores is too big (more than 10,000 books) to allow authors who are not very best sellers to stay on tables enough time. So, we can say it is quite difficult to live like a writer. A little easier, to make a living writing children’s literature.