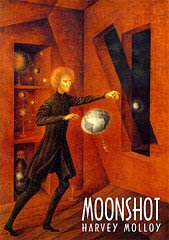

Harvey Molloy is a Wellington teacher and poet whose first collection of poetry, Moonshot, has just been published – which made this a very good time to interview him by email.

First of all, congratulations on the publication of Moonshot. What can you tell me about the book, and where can interested readers find more information, and copies to buy?

Moonshot is my first book of poems. It’s divided into two sections. The first ‘Gemini spacewalk’ explores space, the universe, and how space features in the imagination. The second section ‘Learning the t’ is down to earth and concerned with travel, particularly my time in Singapore, and family relationships. The book is orchestrated to follow these themes but some poems don’t fit this pattern and I’ve included them because I like the poems. You can find out more about the book over at my blog at http://harveymolloy.blogspot.com and you can order the book from me from the blog.

Moonshot is your first poetry collection: a significant milestone for any poet. How long have you been working towards having this first collection published?

I started to write poetry again back in the mid 90s. In 2000 I moved to Singapore to work at the National University of Singapore. At this time I became interested in Asperger Syndrome, which is an autism spectrum disorder, and wrote some research articles in this area. After Latika and I finished our book Asperger Syndrome and Adolescence: Looking Beyond the Label, which was published in 2004, and moved back to New Zealand, I began to focus more seriously on the poetry. About four years ago I decided that I had enough poems published in different journals to put together a manuscript. So I guess I’ve been working on it seriously for four years or so although it’s been on my mind for around eight years.

They say “It’s tough oop North”, and if it is, the two of us should know, since you were born in Oldham and I in Grimsby. Though you’ve lived in many countries since then – the States, Singapore, New Zealand – do you think there’s a Northern English sensibility to your poetry?

Yes, I do. The northern sensibility comes through in the sound of the words. Living right on the Pennines also has a powerful effect: the northern landscape is incredibly varied: it’s both ruggedly rural and horribly industrial all within the same borough. I think that there’s a particularly Manchester sensibility: it’s part humour, part gothic horror, and part self-parody. Lancastrian is the only accent that sounds as if it’s mocking itself or refusing to take itself seriously whilst also sounding out the very roots of the language. And I also think there’s a ‘Lancastrian male hysteric’ element in the culture; northern masculinity is very different and more feminine than the ‘kiwi bloke’ culture: you see this in Billy Liar, in Alan Garner’s novels, in Amis’s Lucky Jim, and in bands like The Fall, Joy Division, Magazine and The Smiths, etc.

We have something else in common: an interest in science, and in science fiction. I was intrigued and impressed to see that you’ve put the science and science fiction poetry up front in “Moonshot”, whereas in my books, it’s been tucked discreetly down the back. What made you decide to put this section first?

Part of this has to do with Helen Rickerby’s advice. I sent an early version of the manuscript to her and she suggested that I organise my material more thematically and write more about space. Although all the threads were there until I had her help I couldn’t see the shape I wanted. I’m not that fixated on SF or space – the new work is different – but I am committed to what I very loosely think of as a SF or fantasy sensibility that I clicked on around age 12. I remember seeing J.G. Ballard on a BBC book programme when I was 13, talking about his novel Crash. It just reprogrammed me in much the same way that Alan Garner’s Redshift changed my life. Garner’s and Ballard’s work aren’t SF or fantasy but they are deeply concerned with ‘psycho-landscapes’ or unusual geographies. I wanted the astronomical poems up the front as many poets write about their families and their childhoods but few write about astronomy.

When I jotted down the recurring themes of this collection, the words “astronomy”, “history”, “geography” and “myth” appeared. Have I made them all up? Have I missed any? Why do these areas especially interest you?

No, I think that’s accurate but “history”, “geography” and “myth” are also connected with family life. I’m married to an Indian New Zealander and part of me lives in an Indian world and this hopefully comes through in some of the poems. In some ways, I think each individual is a culture with their own myths and I’m trying to explore some of these myths. But I’m also trying to include a variety of different voices and concerns in the poems.

Which poets have had the most influence on your work, and which poets do you most enjoy reading? (Of course, these might be one and the same.)

The following are a selection of poets I love to read and who have moved me: Hone Tuwhare, James K. Baxter, Elizabeth Smither, Sylvia Plath, Seamus Heaney, T.S. Eliot, Adrienne Rich (marvellous), Philip Larkin, etc. and I’m particularly fond of Alistair Paterson’s Qu’appelle (talk about a SF sensibility: Wellington gets nuked!). Recent books I’ve enjoyed are Sue Wootton’s Magnetic South and Helen Rickerby’s My Iron Spine.

How about prose writers?

Alan Garner’s an amazing writer and I think Neil Gaiman’s brilliant: it’s a pity that Gaiman’s film work doesn’t match his prose. And Samuel R Delany’s Dhalgren has a lot to answer for! I also enjoy reading good science writing and have wide ranging reading habits: I’m currently on the last chapters of George Eliot’s Middlemarch and next up will be Mary McCallum’s The Blue.

A tough one to end on: if you had to choose three words to describe your writing, what would they be?

On the line